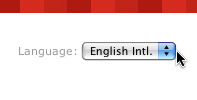

I was on the Boingo Web site recently and I encountered a language picker with “English Intl.” listed as an option, as shown here:

This was not the first Web site I’ve encountered to offer an international English option — and I’m sure it won’t be the last.

Now what does international English actually look like?

In most cases, it’s American English.

For those who prefer British English, this is not the greatest of trends. But it is a trend. And while Boingo makes it obvious through its language picker, there are many more companies who simply use American English as the default English across all English-speaking markets.

Siemens comes to mind. Not only does this German-based company use American English on its .com page, it also uses American English on its .co.uk page.

I can count on one hand the number of companies that pay to have English translated from American to British or vice versa. And in this financial climate, I may not even need that many fingers.

No.

In the years ahead there will be only one flavor of English on most corporate Web sites — just as there will be only one flavor of Spanish (and maybe even one flavor of French).

One day the media will pick up on this as another sign of the decline of the diversity of languages on this planet.

All I know is that companies are trying to communicate with as much of the world as possible while spending as little as money as possible. And even language is facing cutbacks these days.

Do you know that for Adobe:

“International English” (IE) = “American English”

“Universal English” (UE) = “British English”

I really do not know the reasons for this but I could want to create an “Multiversal English” myself, see http://blog.i18n.ro/multiversal-english/

Hello John,

“Now what does international English actually look like? In most cases, it’s American English.”

I disagree. American English is not ‘international English’. British English is not ‘international English’. International English is English that is written for people who do not read English as their first language.

Other names for international English are ‘global English’ and ‘worldwide English’.

“All I know is that companies are trying to communicate with as much of the world as possible while spending as little as money as possible.”

I agree. Therefore, international English will become more popular.

Translation is expensive. International English gives good results with machine translation software. Therefore, in some cases, translations are not necessary. A company can have a website that is written in international English. A translation tool on the website gives readers a real-time translation of the English text.

Free translation tools give satisfactory results. Commercial translation tools let you specify how particular terms are translated. Commercial tools give excellent results.

For more information, see http://www.international-english.co.uk.

Regards,

Mike Unwalla

TechScribe

http://www.techscribe.co.uk

@Sorin

That is hilarious about Adobe: “Universal English”…does that mean that they think British English is only used in space?

We have Hollywood and M$ Word to thank for this. 🙁

A few points need to be settled here. Firstly there is no such language as “British English”, this is a very common misconception due to ignorance. Great Britain and the Channel Islands is, in all rights, an administration made up of many individual countries. Almost all of these countries have their own native language and national identity. To tell a person from Wales that they speak “British English” would be insulting to a great nation that is regaining it’s identity and whose national language has held strong during England’s supremacy.

Point two, how would you account for the people of Republic of Ireland, Isle of Man, Australia, New Zealand (and so many other countries) where English is predominantly spoken and is tightly coupled to the true and correct English language. That being the language of origin, England, also known as English English (as odd as that may look it is a correct term) or simply put “English”. These countries follow the same spelling and grammar as that used in England. Do these people use “British English”? By doing so would associate them with the “British” and I do not see that being the case. They by no means use “International English”, this too would be an insult to their nations. Therefore terminology should be used correctly to define the locale (and we are all familiar with the definition of a locale, right?) .

To conclude, my overall point is that there must never be generalisation when defining languages, “British English”, “International English”, “South American Spanish” etc. are all diffuse and hold no locale ideographies. At all times, language must be identified as a locale when not referencing the language of origin. Therefore, the language spoken in USA is English (United States) it is not English by any means, the same applies to English (Canada), English (New Zealand) and so on, and the same must be applied to all other languages, Spanish locales in particular because they have already been mutilated by misconception and ignorance. I sympathise with the people of Spain who now use a language called “Spanish (International)” — they have lost their identity completely, and Spanish is their language!

This could be debated until we are blue in the face, but the fact that a well defined language has been diluted by illiterate migrants to the North American continent still remains, and they chose to maintain a bastardised version of the English language (mostly phonetic transliteration) and this should never be spread around the world as “English” – call it “American” for all I care, just not English.

Imagine this: Bearing in mind that the English language consists of a vast amount of French words and spellings. How would the people of France feel if the people of England called their language “French”?…

Gary Lefman wrote, “Firstly there is no such language as “British English”, this is a very common misconception due to ignorance.”

‘British English’ is an accepted term. Refer to Quirk, R., Greenbaum, S., Leech, G., Svartvik, J. ‘A Grammar of Contemporary English’. Harlow: Longman Group Limited, 1984. ISBN 0 582 52444 X.

Here’s the essential point I was trying to make: Eventually companies have decide between using, say, “colour” or “color.”

More often than not, on their global Web sites they are choosing “color.”

I would call this American English largely because a man named Webster dropped the “u” a long time ago.

Rather than escape to my nearest bookshop and spend well over 100 Euro for that book first published in 1972 I found a ripped-off copy. It appears that although the term “British English” is used regularly, this is by no means an authoritative document nor does it define an international standard. It is noteworthy that the primary author, Randolph Quirk, who was born and bred on the Isle of Man and is therefore not “British” and very quickly it is noticeable that the book is not written in English English. So instantly this plays into the hands of the ‘tautologous’ rhetoric that is enjoyed by the authors of the Wikipedia entry for “British English”: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_English. I reiterate, there is no such _language_ as “British English”. When referring to Great Britain, the predominant and overbearing country of the three is England and the official language (if not begrudgingly) of the three countries is English as used in England. My argument is not to delve into the origins of English, not how the English language is used or misused within England, nor is my statement to belittle the people of the United States of America and the flavour of English used today or how the two languages differs. My firm belief is that a mutilated version of the English language must not be spread around the world and be called English, plain and simple. It must be referred to as either American, American English, English (United States) and under no circumstances should English, the language of origin, be effectively swept under the carpet and called “British English”; it is inane. >:-)

Incidentally, a quick browse of the book proves to be an interesting read — after running it through the spell checker. >;-)

I think Gary’s points are valid however we do not have the luxury to create multiple version of English for different markets. Thats why it gets lumped into British English and American English (or more often than not, the latter only).

That said, I did see a vending machine here in Japan that had been localised to a very fine level:

– Japanese

– English

– Chinese

– Korean

– Spanish

– Kansai-ben*

*Kansai-ben is the local dialect. It is a bit like offering ‘Scouse’ or ‘Brooklyn’ as a language option.

I do not know if any of you guys have read 8W8 – Global Space Tribes, http://www.8w8.com. In one of the chapters – I do not remember which one – it does cover the aspect of languages melting together and in a way finding a denominator, depending on a digital tribes consensus. Very interesting stuff.

I’m revamping the global web presence of a major NGO, and we’ve got 12 countries regularly publishing in English (of some flavor). So this is a pretty interesting topic for me.

Questions:

Why do you say there is a trend towards American English?

Has someone done research on this? Or is this a personal observation?

I’d love to know.

I think people writing for the web go for the American spelling of English words as readers from Britain are far more comfortable with reading American English as they are exposed to it all of the time.

American readers, who form the largest English speaking audience for most companies, will find their reading disrupted as the British spellings will be far more noticeable to them.

There is probably something here in that websites, primary used as marketing tools, want to present themselves as having empathy and something in common with their audience.

That doesn’t make it right! Just my opinion on this trend.

For my company, the decision to support both UK English and American English was made simply to increase the amount of search traffic we get from Google and Yahoo. There are a fair number of differences in the way searchers phrase queries – for example, I don’t think an American would “go on holiday” (we’d “go on vacation”), but supporting both forms of English allows searchers from any English-speaking country to find our site.

I’ve even been toying with the idea of doing a translation into “Australian” for our .com.au domain, but I’m not familiar enough with Australian English to determine if it makes sense to do this.

Hi John – Great blog entry! We just linked to it from http://blog.fxtrans.com/2009/02/language-fact-british-vs-american.html.

Congrats on the new job too!

Best,

Andres

We maintain two versions of French web content for both Canada and France, and yes, two versions of English for the UK and the US.

It’s hard to find the right balance between accommodating as many audiences as possible (and enjoying SEO benefits/visibility) vs. what it costs to do so. It’s the age-old question of ROI.

Great thread (and welcome to Redmond, John!) –

Jen Hofer, Lionbridge

Do you know the “language Icon”?

http://languageicon.org/

I hate to say it, but I’m not sure if what Gary says speaks more to me of racism, xenophobia, or arrogance.

What do you call it, then, when you learn to speak a foreign language? I’m from the United States. If I learn French in school, is it still “American”? Will I never be allowed to say I speak “French”? That’s what you’re seeming to suggest.

And it’s not like English in England is the same as it was 400 years ago, either. It’s just as much a bastardization (with a purposeful z) as the language spoken in the US. It is not as though thou still speakest with the second-person singular pronoun.

I’m not so sure about this trend you see towards one flavo(u)r of English. Just have a look a the five largest global websites:

Google, Yahoo, Facebook, YouTube and Windows Live offer both UK and US English!

Several other languages come to mind for which varieties play an important role: Portuguese (Brazilian and European), Chinese (traditional, simplified) Norwegian (Nynorsk and Bokmål) and Spanish (Spain, Latin America).

As more and more websites become multilingual, these varieties will often be supported. Users like to have a choice!

Some 30 years ago the Brazilian subsidiary of a German company was looking for someone who could translate something “into English”. “UK or US?”, was the question. “Doesn’t matter, really” —they answered” — This is for mainland China and we don’t really know what brand of English they speak. Just make it really simple. I am afraid nobody knows much English over there”.

In addition, US × UK goes far beyond the “color × colour” issue.

As a participant in an international project with zero budget for translation, I can attest that there is another variety of English out there which one might call “chaotic English.” In our case we mostly have Americans like me who wouldn’t have a clue how to write British English and Continental Europeans who mostly grew up with British spellings in the classroom and American pop culture outside it. We do the best we can but at times we literally have “program” and “programme” on the same page. Give me a €250k editorial budget and I’ll straighten it right out.

As a participant in an international project with zero budget for translation, I can attest that there is another variety of English out there which one might call “chaotic English.” In our case my colleagues consist of Americans like me who wouldn’t have a clue how to write British English and continental Europeans who mostly grew up with British spellings in the classroom and American pop culture outside it. We do the best we can but at times we literally have “program” and “programme” in the same document. Give me a €250k editorial budget and I’ll straighten it right out.

I think this conversation is hampered by a confusion between descriptivist and prescriptivist points of view. Gary Lefman’s search for an “authoritative” definition is in my opinion pointless, since unlike the academies which govern French and Spanish, English has no authoritative body to make such decisions. In my personal opinion that’s a good thing, because I don’t see how the speakers of French or Spanish (particularly not those from Montreal, Mauritius, Mexico or Montevideo) have ever benefitted from such an authority, but maybe that’s just my postcolonial bias.

I do agree that there are many Englishes, not just two. How many one chooses to translate into should be a practical decision, not a political one. It may be that in contexts where the primary goal is to convey factual information, even one target English is sufficient provided that one avoids a few linguistic landmines and pays sufficient attention to localization issues that go beyond the linguistic (e.g., laws, governmental institutions and which side of the road to drive on). On the other hand, where affective engagement with the material is the primary concern — i.e., in marketing — one might need a dozen or more Englishes for global coverage.

Argh. Damned double-paste. 🙂

just a thought as i was researching something else (stumbled upon this site). As a brit i don’t really care about the spelling – the americans simplified it, and good for them. Indeed, if anything perhaps more UK spelling is creeping into American discourse when previously it was pristine…

anyway, that’s not the point. The point is not spelling, it’s semantics. The fact is the world is speaking, increasingly, English, and the way a language is constructed shapes the way we – literally – interpret the world. and in this case it’s in English: Americans may wish to point-score on the spelling of “colour” but what’s more relevant is that for all its independence, constitution and aircraft carriers, the US is simply a constituent part or the English-speaking “universe”.

Cheerio!